Basso Continuo & Internet Search

Embracing harmony and imperfection in the information age.

In the age of AI and Silicon Valley jargon, the messianic tone of tech messaging falls flat, as though it has been pulled straight from PowerPoint pitch decks designed for venture capitalists. Media channels are bombarded with binary op-eds that either claim AI will change everything or do the exact opposite. But somehow on both ends of the spectrum, the messaging doesn’t seem to reflect reality.

For both technologists and regular users, AI indeed feels more dramatic than other recent "this will change everything" technologies, namely cloud computing, 5G, and blockchain. This is mainly due to its issues with neural network explainability and comprehensibility, combined with how user-facing it has become. However, from the user perspective, the conversation around AI today is lacking because the metaphors are opaquely self-referential. Understanding AI in terms of other recent technologies seems inadequate.

Internet search is likely to be the primary domain where people will first explicitly encounter AI in their day-to-day lives. Search also appears to be the most significant commercial avenue for changing our perception of information communication and research. It also impacts our ability to discern fact from fiction. The story of AI and internet search, or the chatbot vs. Google, reminded me of a world and a transformation I know intimately: music notation, and specifically, the transition from Baroque to Classical notation. Bear with me as we go on a brief musical history lesson.

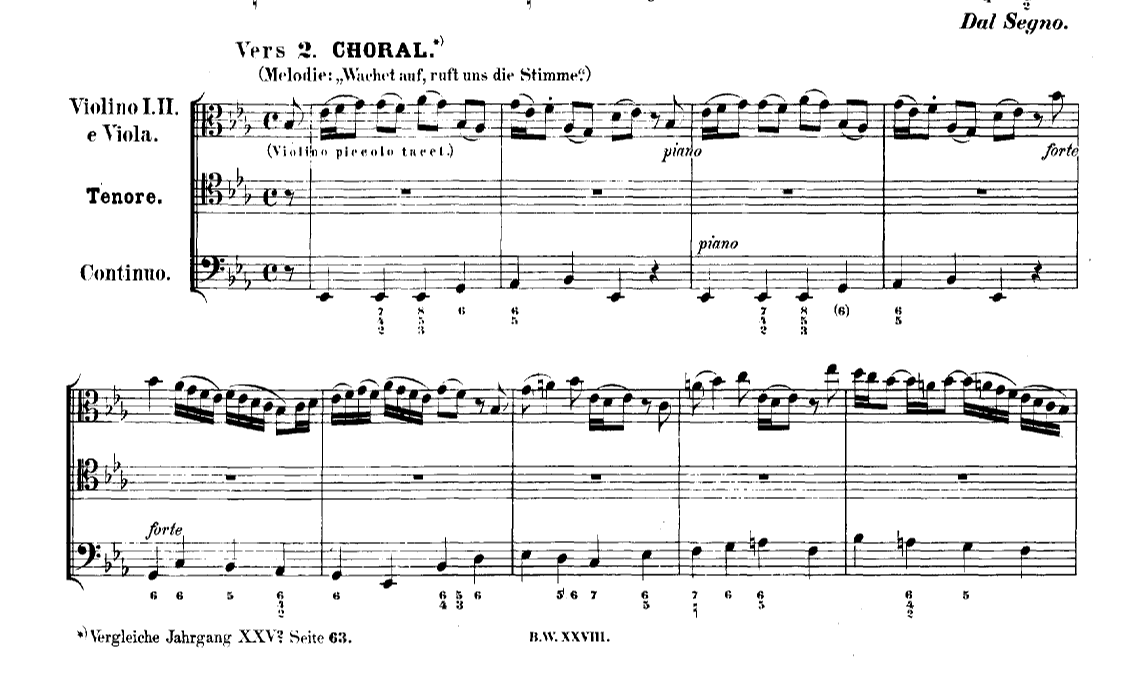

In the Baroque period (~1600-1750), Basso Continuo (or Figured Bass) became popular for striking a new balance between composition and abstraction. This notation system, with its fully written bass line and numeric shorthand for harmony became the industry standard framework for many important composers. Here’s an example from J.S Bach’s BWV 140 :

Those numbers under the bass line indicate how these notes relate to the chord that should be constructed on top of them. When there’s no number, it’s implied that the chord is the natural triad for the specific note in that scale (in C major, C would be C major, and A would be A minor). This notation system worked well because it empowered its users. It wasn’t the sleekest or streamlined way to write music, but it provided features that were tailor-made for the musicians of the time:

The absence of specific instrumentation allowed continuo parts to be played by different ensembles. The harmonic content could be performed on an organ, lute, or harpsichord, while the bass line could be played by instruments like viola da gamba, bass, or cello. This versatility was particularly helpful for church ensembles, which were often comprised of local musicians with inconsistent instrumentation.

The shorthand numeric system for chords allowed continuo players flexibility in interpreting specific voicings, tailoring them to their chosen instrument, ensemble, venue, and other performance aspects.

Baroque-era musicians often possessed a diverse skill set, blurring the lines between performer, arranger, and composer. Thus, they were equipped to handle the contextual harmonic notation and appreciate the interpretive latitude that it afforded.

With the dawn of the Classical period (~1750-1820), the Industrial Revolution brought economic prosperity and with it the democratization of music education. Printed sheet music brought music into many new households all across Europe, but Baroque notation was replaced by spelled-out harmony and additional notation components, making music notation a lot more explicit, and therefore, leaving less room for confusion (or interpretation) by the performer. Here’s an example from Mozart’s Piano Quartet in G minor, K.478:

Classical notation was a commercial success because it made sophisticated compositions accessible for inexpert musicians to casually perform, but it raised questions about the nature of music and the musician's interaction with the notation.

What effect does "spelling out" the harmony has on the musician's interaction with the notation?

Does allowing room for interpretation invite mistakes, or does it foster deeper understanding and improved performance?

Which of these systems is superior for the user (musician), and which is more advantageous for music? Are they distinct or equivalent?

With these questions in mind, let's fast-forward to the present and draw a parallel transition to our contemporary world of internet search, and its disruption by AI. On one side, we have the incumbent Google, and on the other, the disruptor, ChatGPT. This is an example of how the two systems react to the same input “How should I choose running shoes”.

Google:

ChatGPT:

By examining these two systems, we can now modulate the questions to those raised by the music notation transition.

Is ChatGPT's response deemed more accurate due to its explicit nature?

Does a user's personal preference for selecting which link (or multiple links) on Google, and their interpretation of the information, create potential for misinformation or improved information?

Which of these systems is more advantageous for the user, and which is superior for information dissemination and education?

The answers to these questions may emerge gradually over the next decade, or perhaps more abruptly. However, by examining the evolution of musical notation, we can glean some insights that might hint at relevant predictions. The classical notation system encouraged a broader range of participants in the craft, which subsequently led to more specialized professional roles for musicians. Performers, composers, and arrangers are now distinct disciplines with fewer overlap. As these disciplines evolved, we have witnessed an increase in music created from their focal points and techniques. Some might argue that the storytelling and expressive aspects of music have often taken a backseat to more easily relatable technical aspects that inspire and engage these amateur musicians.

If history and the transitions and democratizations of systems like basso continuo to classical notation offer any lessons in the information age, we should not expect an increase in accuracy or comprehension but rather an increase in perceived accuracy.

All communication of information is an approximation; the words in a poem can approximate feelings, but they are not the feelings themselves. The word for a chair can describe a chair, but it is not the chair itself. Systems that provide more explicit information and detail accomplish just that—they make things more accessible, but not necessarily more intentional or accurate.

Systems that embrace approximation, such as Google search and basso continuo, allow users to learn, express personal preferences, and, most importantly, concentrate on asking the right questions instead of relying on the false certainty of a definitive answer.